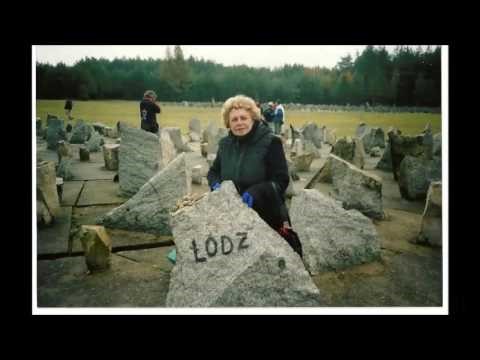

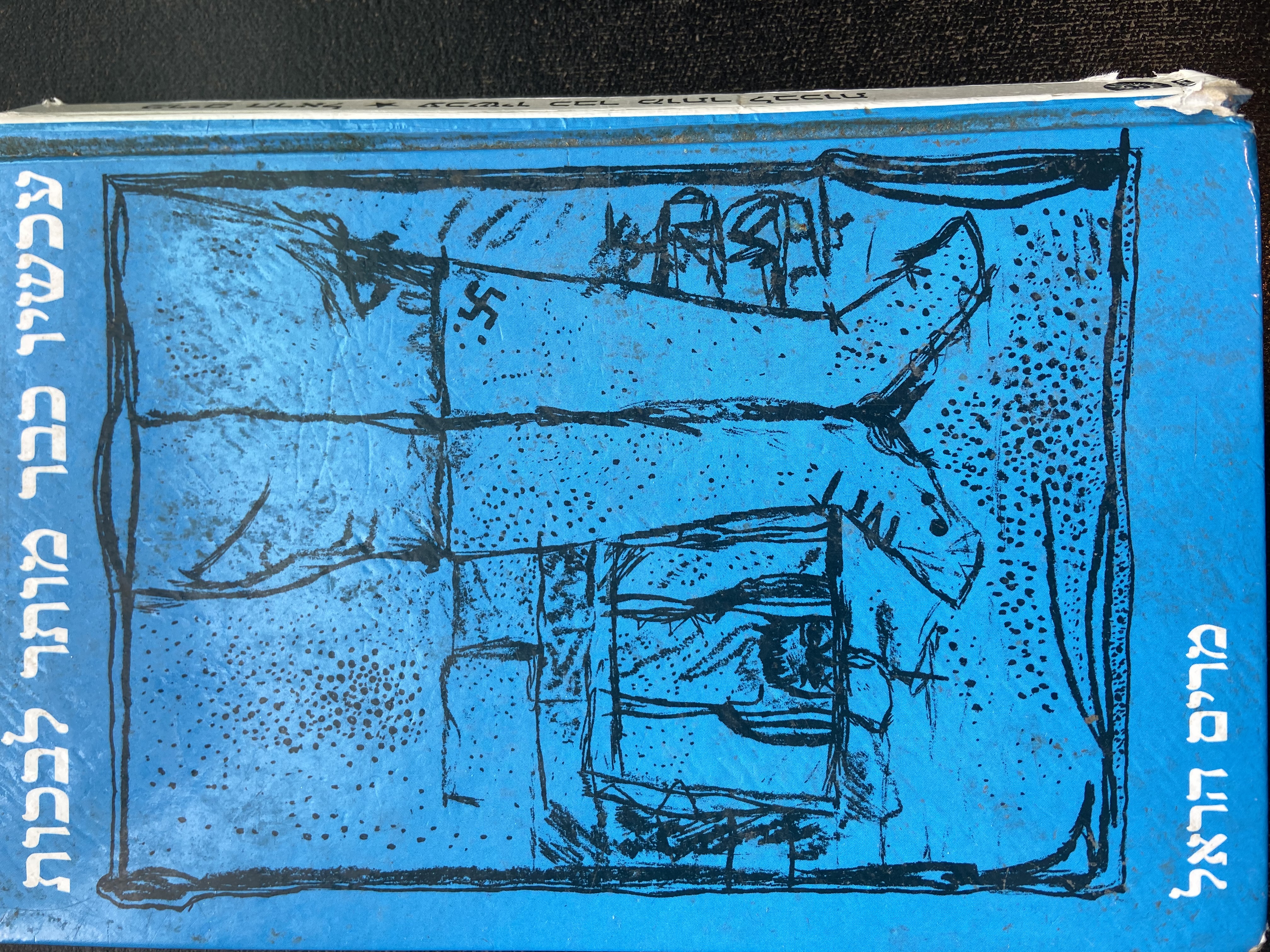

Miriam Harel, Gabriel and Sara Goldberg's sixth child, was born in Lodz, Poland in 1924. The other Goldberg children were Israel (born in 1910); Rachel (1912); Rosa (1916); Paula (1918); Hanka (1920) and Yitzhak (1926).

The Goldberg family was Orthodox. Miriam says that the Jewish community was very cohesive, and that cohesion radiated to the friendships between the children and created for her a beautiful and happy childhood. She remembers: "I was a naughty girl and at the same time very curious. I always wanted to know everything, so much so that even when I was in kindergarten I would sit with my brother Israel to read and study Torah, and because of that, when I went to first grade and started school, I already knew how to read and write. I was so good that they decided to have me skip a grade. I immediately started studying in the second grade."

In 1939, the war broke out. "I remember when the war started, I wasn’t afraid. I believed that my parents would always protect me no matter what happened. I don’t know why I felt that way. Maybe it was the child in me. I just had a lot of confidence."

One of Miriam's first memories of the war was that she was forced to wear the yellow “Star of David” patch. "I was already a 15-year-old girl then. I wasn't really upset. I had had a gold necklace with a Star of David for as long as I could remember. My father bought it for me when I was really small: a Star of David in a circle. I wouldn't go anywhere without it. I was always proud that I was Jewish. I had a friend who had been given a Star of David necklace by her own father. And I remember that on the first day we were forced to go with that patch, we both took off our necklaces and wore the patch with pride! I was not ashamed of the yellow patch. I was proud of it! The only thing that bothered me was that I had to make sure that I had that patch on every outer garment I wore. And I really took care to put the patch on every outer garment. I just did not want to get into trouble or to be stopped on the street. You see, from my point of view, I was just a 15-year-old girl. I was not too aware of the war or its meaning. The only thing I resolved for myself was that if during the day I should meet some Germans, I would define that day as a bad day for me and if I did not meet any Germans that day, I would define that day as a good day for me. All in all, I tried very hard to maintain a good mood and to be happy".

Miriam says that as the war progressed, she was exposed to greater difficulties and challenges. "Later in the war, things started to change for me. My family and I were thrown into the (Lodz) ghetto. The conditions in the ghetto were difficult and terrible. Unfortunately, my parents could no longer take care of us. Their inability to function made me "the responsible adult" and so, together with my brother, I would take care of the household. I found a job at a vegetable shop in the ghetto."

Miriam says that once, when she was walking about in the ghetto, she came across a group of orphans. "I decided I would take care of them and from then on, for me, they were my children. I took care (of them), loved and played with them. Today when I look back, (I know that) that helped me to stay sane in that terrible place, to find meaning in my life so that I could endure the nightmare".

While in the ghetto, Miriam joined the Gordonia youth movement, where she learned about the values of Zionism and about the Land of Israel. Then, she began to dream that if the day came and the nightmare ended, she would build her home in the Land of Israel.

In 1942, everything became even more terrible, says Miriam, "when the Germans started to execute the 'final solution' and in order to do that, they started to eliminate the Lodz ghetto, where we lived, by transporting Jews to the death camps. My father was the first of us to be sent to those death camps. He was murdered in Chelmno in 1942. Shortly afterwards, I too was deported. I arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. I was completely alone and did not know what to expect. I remember when we got off the train and stood for 'the selection', I found myself standing in front of Dr. Mengele. It's hard for me to understand why but when he asked me how old I was I just lied and said I was 20. I had almost never lied before. I was really shaking and scared when I lied, but luck was with me and Dr. Mengele smiled and sent me to the right (to the hard labor line), which later turned out to be the gift of life for me. Toward the end of the war, I was sent to Bergen-Belsen and from there to the town of Mehltheuer in the heart of Germany. (There), I was forced to work in an aircraft parts factory for the benefit of the Nazi military effort which was already about to fail. I was desperate and exhausted. But the hope of being reunited with my family kept me going and sustained me with my last bit of strength, until I was liberated by the Americans on April 16, 1945. That date became my second birthday".

After the war, Miriam returned to Lodz, hoping to find more survivors from her family, and indeed, miraculously, she found her sisters, Hanka and Paula. "After the liberation, I went to Italy and lived there for about two years. In Italy, I met my husband Joseph Skotsendak. We were married on November 27, 1946. We tried to immigrate to Israel on the illegal immigration ship 'Moledet' (Aliyah Bet) in 1947, but when we arrived at the port of Haifa, the British captured us and exiled us to the military camp in Cyprus, where we stayed for about 13 months. Our eldest son, Haim, was born in the camp on March 10, 1948. We came to Israel as part of the 'Aliyat HaTinokot' program and on April 26, 1948, we became residents of the country and I felt I had fulfilled my dream."

Miriam continues, "At first, we lived in Kibbutz Mizra. After about a year, we moved to Kiryat Bialik and from there we did not move anymore". Miriam has three children, nine grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. "My family is my victory over the Nazis!" she says.

It is very important for Miriam to convey a message to future generations: "I want to ask in every possible way, to remember that in the end we are all human beings. Always be good people, compassionate towards those around you, especially towards our fellow Jews, your brothers, and if there is anything important in life it is to learn, learn and learn some more. That's the only way you can grow as a human being. That's the only way to overcome ignorance and hatred".