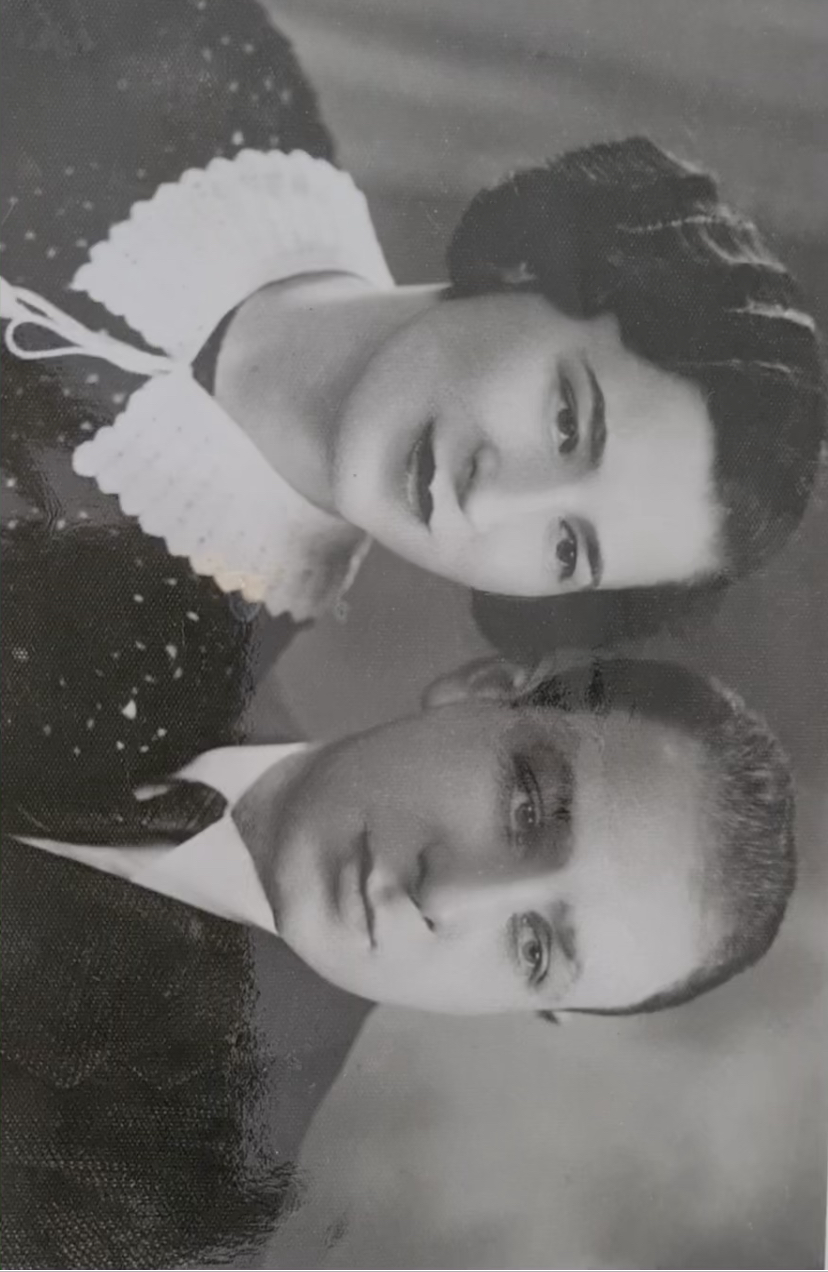

Tammy Lavi is the daughter of Oizhen (Gedaliah) and Hannah-Gittel Blass, and the sister of Yerachmiel. She is married to Shlomo Lavi, with whom she has two children and six grandchildren.

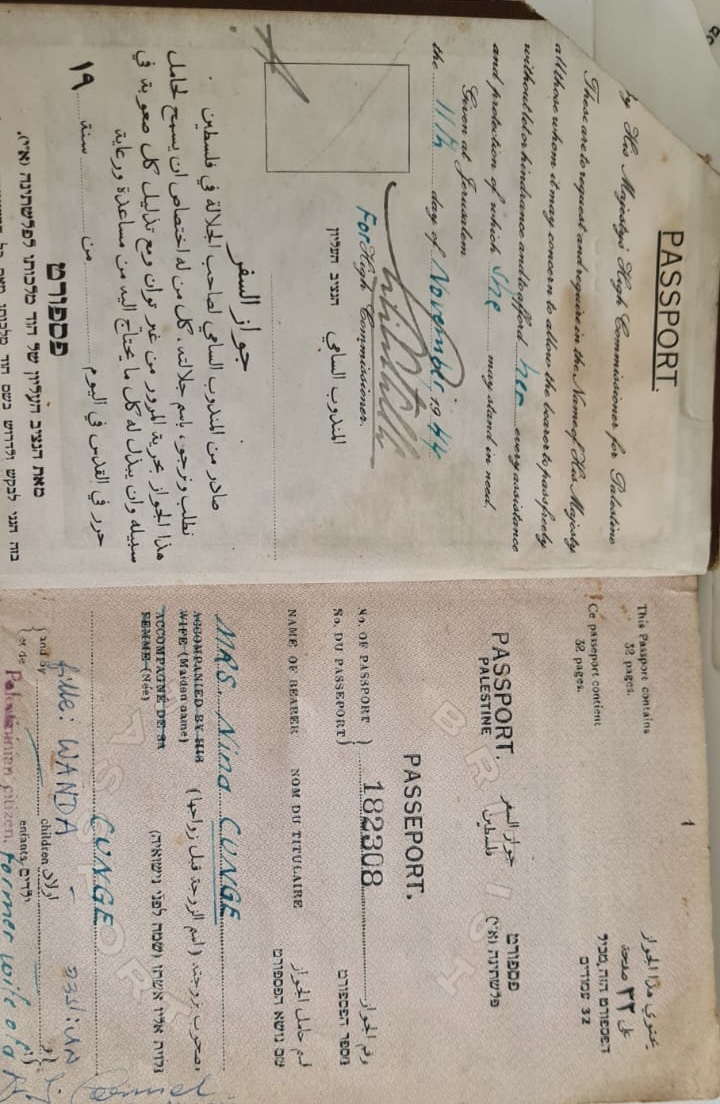

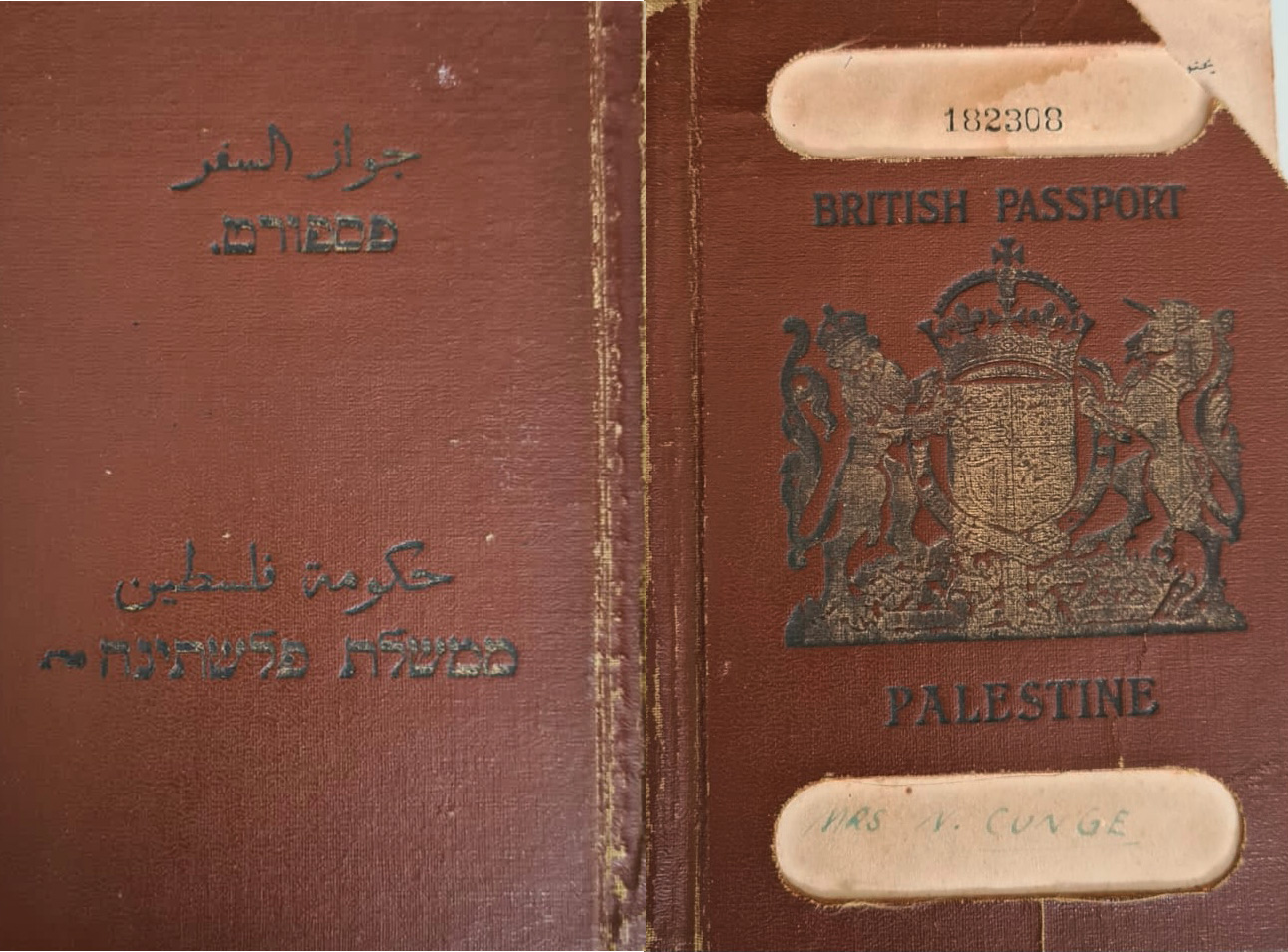

"My story," says Tammy, "begins in the Lodz orphanage when I was nine or ten. One morning during Hanukkah in 1948, a woman named Nina Cunge came to take me to Eretz Israel. The caregivers had prepared me the day before 'my mother' arrived. That was quite common after the war [when] every day, parents who had survived came to claim their children and take them away. I was sure the same thing was happening now for me too: 'my mother' was coming to pick me up. Of course, I was excited! I had no memory of my mother. She had handed me over when I was really little.

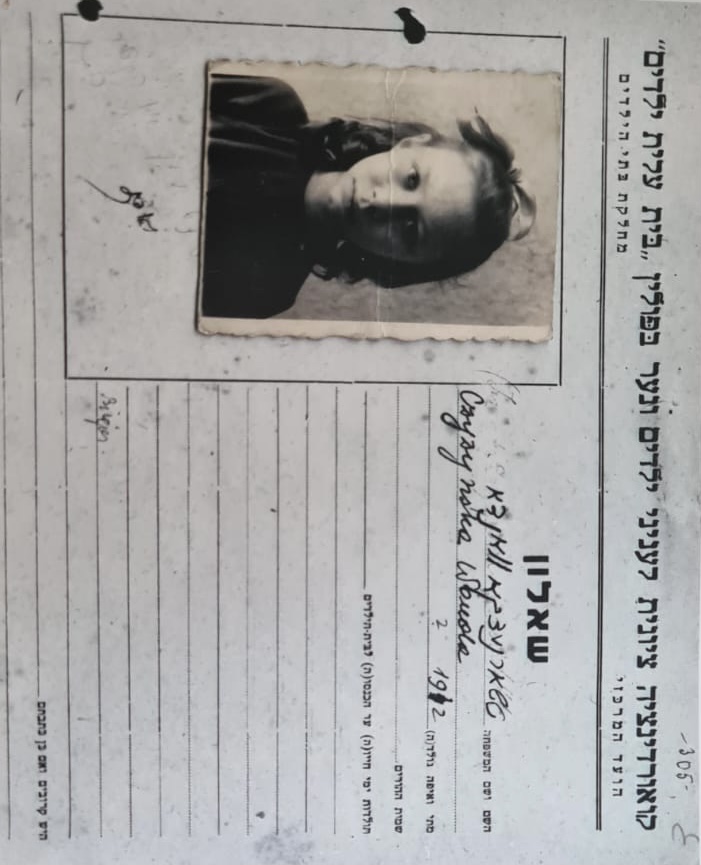

In fact, the next morning 'my mother' arrived – a woman named Nina Cunge. Nina picked me up and told me that we were leaving for Eretz Israel. Eventually, I learned that she was not really my mother and that her goal was to create a living memorial to her own mother who had perished in the Holocaust. We arrived in Eretz Israel on January 1, 1949. I remember very clearly the trip from the airport, from Lod to Haifa.

The first thing Nina asked me to do was to change my name from 'Wanda', my Polish name, to 'Tammy', an Israeli name. In addition, she asked me to forget everything I remembered from Poland. That seemed strange to me, but I was an obedient girl. I remember once when we were walking around in Haifa, I was sure I heard someone shouting my Polish name, 'Wanda'. Of course, I looked around to see who was calling my name. At that moment, Nina, 'my mother', shouted at me: 'You should not turn around and pay attention to every voice'. Again, it was a little strange. I didn't understand what the problem was if someone knew me. Even stranger, at the end of that year, we moved from Haifa to Jerusalem, and I started school at the Hebrew Gymnasium.

One of the things I was exposed to when we lived in Jerusalem was the Scout movement. I really liked going to the Scouts. It was my life. I liked the dancing after the activities even better than the activities themselves. Once, the dancing was so much fun that I didn't notice the time and I was late getting home. 'My mother's' reaction was extreme: she didn't open the door for me at all, and my punishment was spending the whole night on the stairs outside and thinking about what I did. I asked myself 'What did I do? I enjoyed dancing!' When morning came, she sent me to school as usual, and again I asked myself how a mother could behave like that with her only daughter.

'My mother', Nina, had a very good friend in Haifa named Regina. I always envied Regina [because] Regina symbolized in my eyes what a family is. Regina was married and had a child, a whole family. On one occasion, I asked 'my mother', 'Where is my Dad? What happened to him?' That question made her very angry. She told me he had died in the war and told me not to ask about it anymore. My relationship with her deteriorated rapidly, and during that time I decided I no longer wanted to stay with 'my mother', Nina. I asked Regina to help me convince Nina to enroll me in a kibbutz as a boarder. Regina really devoted herself to the task and succeeded, and the following year I started to study at Kibbutz Beit Alfa. I was at Beit Alfa for a year. I didn't really connect with the kibbutz or the fieldwork, and after a year I was informed that I was not suitable.

I moved to Kibbutz Ramat HaKovesh. I really liked Ramat HaKovesh. There were a lot of familiar Polish aspects, which helped me a lot to feel comfortable. In addition, the atmosphere there was really fun. Sometimes, we would run off from the kibbutz to Ra’anana for parties. At the end of that year, I was drafted to the military. I was very excited! I must point out that during those years, the breach between 'my mother' and me made me wonder about the real nature of the relationship between us. Because I just never felt like I belonged, I always asked myself who I was.

I remember that one of the first times that I asked myself this question was when I accidentally saw the identity card of 'my mother', Nina.In her ID, she was registered as Nina Cunge, born in Lodz, divorced, and immigrated to Israel in 1933. The information didn't make sense to me, because I was born in Lodz in 1939, when Nina was supposedly already living in Israel. When I mustered up the courage and tried to ask her about it, she replied that it was none of my business and there was no point in talking about it.

Going back to my army service: I enlisted together with my classmates from Beit Alfa. I served at the Ramat David base [where] I met Shlomo, the person who later became my husband. As our relationship deepened and the love between Shlomo and I became serious, we decided to get married. When I informed Nina of our plan by phone, she didn't even invite me back home for a celebratory meal, [but] to a café, like two strangers, and again the question arose, 'Who am I for her?' I felt she was really treating me like a stranger!

Shlomo and I got married. A year and a half after the wedding, when I gave birth to my eldest son, was the first time [Nina] showed any interest [in us]. She invited us to her home. I was glad that our relationship was becoming warmer again and, indeed, I started to see her, but not just to renew the relationship. I also visited to find out the truth about myself. At that point, I already knew and felt that she was hiding something from me. There were too many questions. One of those times when I traveled to Haifa, I went to the Talpiot market to buy onions. Suddenly, someone approached me and said 'I know you. You're Wanda'. I told her she was wrong [and that] my name was Tammy. She told me, 'It's not true. I remember you. I was your tutor at the orphanage in Lodz. If you don't believe me, come see me. I have pictures that will prove it to you.' Wow! That was a shock. It intrigued me so much: here was someone who knew something about my past. I decided to visit her [and] she really did show me pictures of myself. I was just shocked! It was true!

The woman gave me another detail: she said she remembered that I was taken from a convent. That was already a real bombshell, but she actually proved to me that she was telling the truth. The puzzle started to come together. I began to realize that I really didn't know the whole story, but from then on, every time I went to visit 'my mother', Nina, I searched for my past. The question just burned in me: I wanted to know who I was. One of the times I visited her, Nina needed to go to the dentist. That was my opportunity. I was finally left alone in her house. I just started looking everywhere. I didn't know what, but I just wanted to find something.

When I moved her drawing table, I found two handwritten notes in her handwriting. On the first note was written: 'In Zamość Monastery in the Lublin area, a convent of sisters'. On the second note it said: 'Czenka Czrenska city near Warsaw'. That was a real breakthrough, but I still needed more information. Luckily, I knew there was a priest serving on the French Carmel [in Haifa], and his name was 'Father Daniel'. I contacted him. When we met, he told me that exactly four months earlier a nun had come to visit him from that very convent. He promised to try to help and indeed he did help me. He sent a diplomatic message to that convent in Poland, with a request to help by sending details if they knew anything about my case.

'Bogumiła', the mother superior – whose name means 'God's favorite' – was a special personality, exactly like her name. During the war, she saved four Jewish children, two boys and two girls. She cared so much about the children that she did not allow any of the nuns to shower the boys, so as not to reveal their Jewish identity (the boys were circumcised). During the whole time [that they stayed in the convent], she bathed them herself.

When she received the letter from Father Daniel, she called the nuns together and asked if anyone remembered a girl named Wanda. One of the nuns replied that she remembered that there was a girl in her group by that name. Another nun said she remembered that there was a girl by that name and she even remembered that she had braided her hair. A third nun mentioned that she remembered that there was a woman who always worried and checked on Wanda's well-being, and every week she would even bring her something sweet. The nun even remembered that the woman lived in Hrubieszów.

The mother superior used this information and wrote a letter to the pastor of the church of Hrubieszów. In the letter, she asked to check if a woman who was in Zamość during the war attended Sunday mass (the convent is located in Zamość). The pastor replied that there was indeed such a woman [who attended] the church. The mother superior met with that woman and that was a breakthrough. The woman's name was Maria. She told the pastor that during the war she had lived in Zamość (when) she met a Jew from the ghetto who had a son and a daughter. 'We both worked for the Germans in their kitchens', she said. Then, Maria said that she remembered that after they became friends, the Jewish woman told her that she was originally from Włocławek, and that they had been sent by the Nazis by train to the ghetto. The Jewish woman was pregnant and while traveling, she knelt to give birth. Her husband begged the Nazis to stop the train to allow her to give birth properly. After many cries and pleas, the train stopped. The Nazis put her off the train, but her husband and son were not allowed to get off. When she started shouting, 'That's my husband; that's my son!' They threw her son out of the train window. Her husband stayed on the train and then the train left. That Jewish woman gave birth to a baby girl on December 15. (Tammy: 'Today I know that that girl was me, and the woman in the story was my mother').

The woman from Zamość continued to tell the mother superior my mother's story. My mother knew she had family in Warsaw, so she went there and indeed her family helped her and arranged a place for her to live, but it was very hard for her without her husband and her son. Because it was just the beginning of the war, it was possible to send letters. She found out where they were and sent them a letter. She even received a reply, that they were in the ghetto of Zamość and they were okay. My mother decided to reunite with her family and, so, we wt to the ghetto in Zamość, where she also met Maria, the Polish woman who had worked with her in the kitchen. They became good friends.

Unfortunately, my mother never saw my father again. My mother found out that when my father was brought to the camp, the Nazis sent out ten men for forced labor on the first day. Only eight came back alive; two did not return. One of the two was my father.

And so, the months went by. My mother, Hannah, noticed that the situation of the Jews was getting worse every day. Gradually, the Nazis deported her whole extended family, and my mother realized that she and I were next in line. My mother asked Maria to save me and take care of me. Maria was very frightened at first, but at last she agreed. I want to mention that my mother was a very smart woman. When she said goodbye to me and handed me over to Maria, she took care to change my name in the certificates I had. My mother's last name was Czarny, a Jewish name, and my father's last name was Blass, which also sounds like a Jewish surname. So that [the Nazis] would not recognize that I was Jewish, she changed my name to Chernsky. And why Chernsky? Because in Poland, there was a hero whose name was Czernski. But also, the name Czarny, my mother's maiden name, is contained in that name.

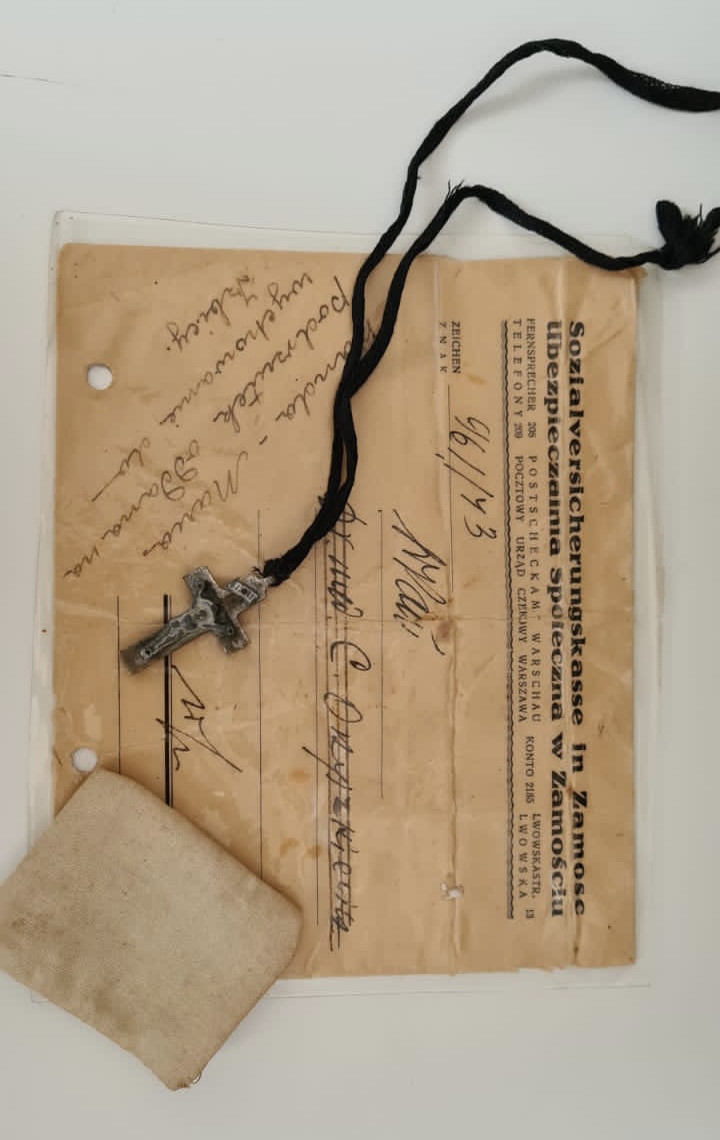

Maria took me to her house and told me not to leave the house by myself. I was a little girl of three years at that time. One day, I could not overcome my curiosity and I went out. Apparently, one of the neighbors saw me and reported me to the SS. They came to Maria's house. Maria said I was her niece. Luckily, the SS soldiers believed her and we were saved, but from that moment Maria was very frightened and because of that – it was 1943 – Maria decided to try to hand me over.

Maria wrote a note, which read 'baptized in holy water and should be looked after'. So that anyone who found me would think I was a Christian girl, she hung a necklace with a cross around my neck and left me near the convent in Zamość as an abandoned child, under the name Wanda Maria. The mother superior and the rest of the nuns took me inside. I was in the convent throughout the war. I don't remember much because I was four or five years old. But I do remember the long corridors. I also remember the gray clothes of the nuns. The nuns were amazing! Always hugging, always smiling. We never lacked for anything. It's funny to say, but I went through the war without a worry. Today, I know that there was another Jewish girl in the convent who was older than me. She lives near me [now], in the Vardia neighborhood in Haifa.

The situation after the war was really difficult. Many abandoned children roamed the streets. The convent appealed to the local population to come and adopt the children who had lived in the convent during the war, in order to make room for the abandoned children who appeared after the war. So, one day a woman came from Izbica, Mrs. Shimanska. She and her family adopted me. They were a really poor family. We lived in a one-room hut: I slept with the mother, and the father slept with the son.

A few months later, two men came to their hut, and I heard Mrs. Shimanska, the woman who had adopted me, crying. I was intrigued. I started listening and I heard the men say to Mrs. Shimanska, 'She's ours. We must take her'. Those two men were members of the Coordination. The Coordination was a Jewish organization meant to redeem the Jewish children who had survived the war living in Christian homes and in monasteries. Mrs. Shimanska did not want me to go with them. She had bonded with me and I with her, but we had no choice and so I found myself in the hands of the Coordination which sent me to the Lodz orphanage."

Tammy returns to the results of Father Daniel's inquiries: "The answers I received amazed me, and I waited for the opportunity to travel to Poland to meet the mother superior and Maria. In 1988, I met a young historian named Eva who was researching 'monastery children' in the Holocaust and, with her encouragement, I flew to Poland for the first time. (I could not go before then because Poland was still communist.) We went to meet Mrs. Shimanska, an old woman, in Izbica. Eva, the historian, asked her if she remembered me. She replied, 'Of course, she was my daughter. How could I forget?' That was such an exciting meeting! I met such a simple woman, but with a very big heart. From there, we went to the convent. Wow! It was so exciting! There are no words to describe it. It made my day!

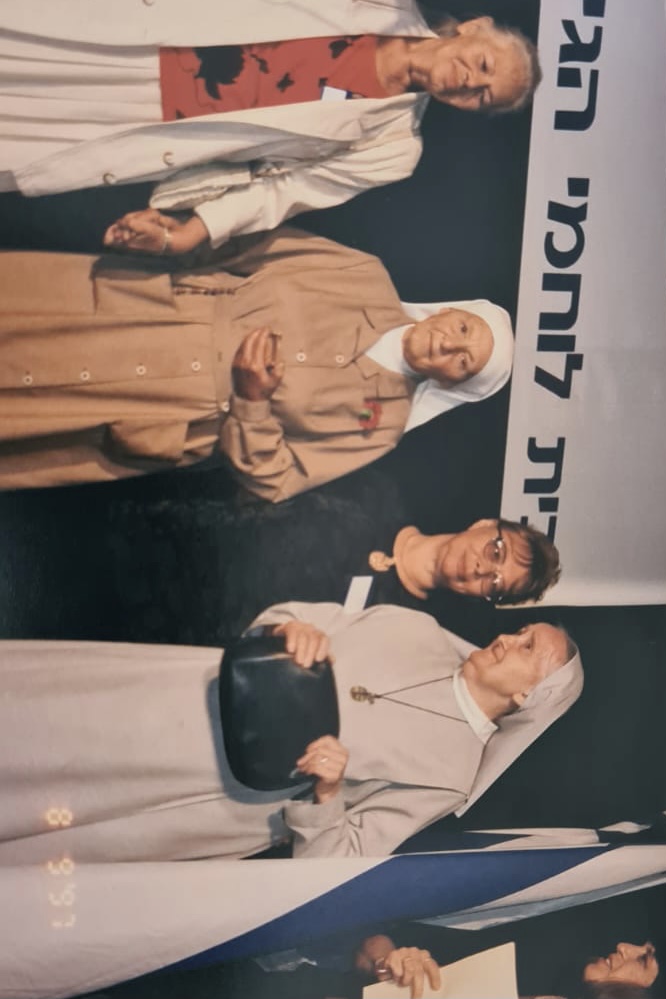

When I got to the convent, Bogumiła, the mother superior, was waiting for us. Outside, she hugged me so tightly! Wow! Suddenly, some nuns shouted, 'Our Wanda, our Wanda!' We went to the dining room. I had brought [Bogumiła] dates from Eretz Israel and a new watch. She was excited [to have] dates from the Holy Land and to bless and eat them with enthusiasm. In return, she gave me her watch. To this day, I have it with me. She also returned to me the cross necklace I had had when I first came to the convent at the age of three, in addition to some very personal documents she had kept over the years.

Since 1988, I have traveled many times to Poland and I visited Bogumiła each time. Once, I even visited her with a youth delegation. She asked to speak to them and asked me if I could translate. Of course, I said 'yes'. She said, 'I want to approach and hug you one by one. You are our brothers and I love you!' At the end of the conversation, the nuns sang 'Haveinu Shalom Aleichem' to us ['We have brought peace upon you']. It was very exciting and suddenly a long line of teenagers was formed to embrace the mother superior. She was so excited!

When I returned from my first trip to Poland, I told my story on the Holocaust Memorial Day that year, and spoke on the radio about my 'roots trip' to Poland. At the end, I asked for anyone who knew more details about my story to call me, and I left my number. Surprisingly, I got a phone call. Someone called and identified herself as my cousin. She told me that we were originally from Włocławek, and that she had been on the train to the ghetto. She remembered how my mother had been taken off the train when she knelt to give birth. That week, I went to see her in the Green Village to hear and get more details. She told me that my father had a brother here in Israel, and she told me that the family name was Blass.

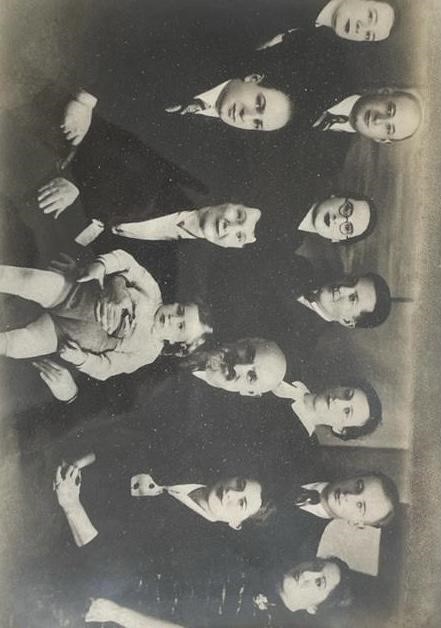

From that moment, I started searching everywhere I could. Eventually, I found someone who helped me find my cousin's phone number. My father's brother had already died. My cousin couldn't believe it. She had heard that all of [my family] including me, had perished. I asked to meet her [and] we met the same day. That was a very strange meeting, but I found out that another of my father's brothers had come to Israel: the first brother in 1925 and the second in 1933. I was so excited to have a family! The next day, she brought her two sisters and they brought pictures of the family, and brought up some memories.

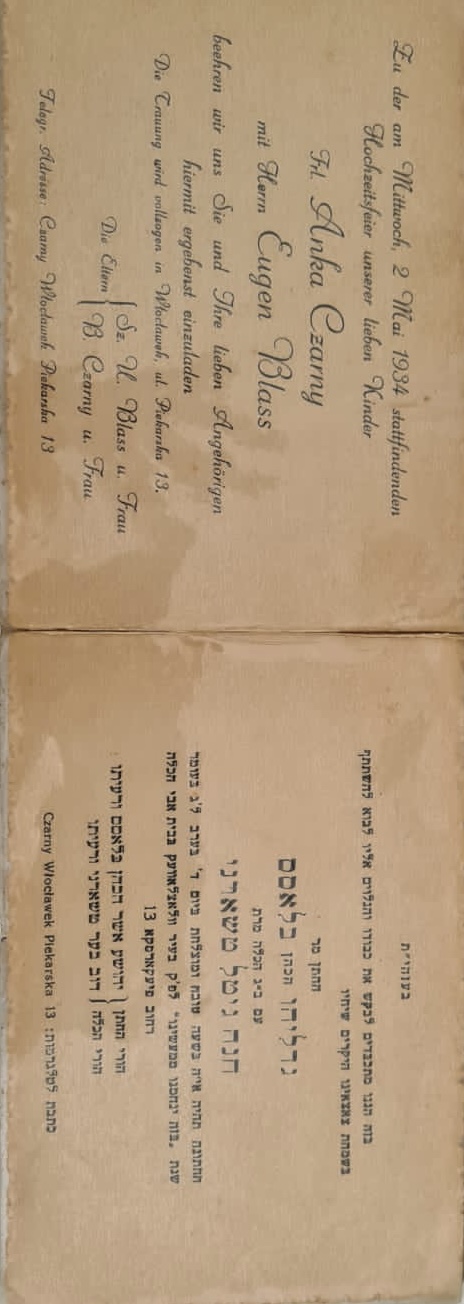

In 1991, my first daughter got married. That was a very big event for me, and not just because of the wedding itself, but because it was the first time family from my side took part. What a great thrill it was that my family was with me, supporting me! The more I found out about myself the more I kept searching until I was able to get hold of the original invitation to my parents' wedding. I shivered when I touched it: I was touching something my parents had touched. I was also able to discover my original name – Margalit Blass – and above all, I was able to find the house where my parents had lived. I remember that when I first entered the house, I was so excited. The house looked as if nothing had changed inside throughout the years. It was an indescribable feeling! When I went up the stairs, I just felt my legs shaking!

At that point, I really felt like I had filled in the puzzle. I was only missing one part. I knew what had happened to my father and I had heard that my mother had been murdered in Belzec, but I didn't know what had happened to my brother. I didn't even know his name. One year, on one of the youth delegation trips that I accompanied to Poland, a student asked me this question. I told her I didn't know. She went to the memorial book of the people who were murdered and start to hunt. Eventually, we found the name Blass Yerachmiel, and I realized that my brother had also been murdered, and at that point, I completed the puzzle.

In 2016, the Ghetto Fighters Museum held a conference of convent children and invited three nuns. I asked that they invite the mother superior [and] in the end, it came to fruition and [Bogumiła] came here, to Israel. I hosted her for a week. We made her feel part of the family. She spoke at the Ghetto Fighters Museum, saying how special this week was for her. Shortly afterwards, I received a letter from the convent [telling me] that the mother superior had passed away. I was glad I had been able to close the circle and give back to her as she gave to me, even if it was only a small thing compared to what she had given me.